In 2017, we heard from an executive who was heading up a team that specialized in mobile and augmented reality-related technology at a large Asian telecom company. She had a troublesome problem having to do with patent monetization—the process of generating revenue from patents—which she couldn’t realistically solve herself. The researchers on her team were highly innovative, regularly filing patents for the new inventions that they came up with in their lab. So far, so good: tech companies encourage innovation; it’s the font from which big profits spring. Companies often even give IP-based rewards—for example, a $5,000 bonus for every patent granted.

But like many tech firms, the telecom company had become a victim of their own prolificness. By now, they’d amassed thousands of patents—so many that it had become difficult to keep track of what, exactly, they owned. And without a comprehensive sense of their patent property, it was hard to say how valuable the technology underlying all that property was likely to be.

Maintaining ownership rights to a patent often runs to thousands of dollars in yearly fees, so the value question was an urgent one. If a patent wasn’t ever going to make—or save—the telecom company money, why were they spending precious resources maintaining it?

On the other hand, letting go of a patent, either by abandoning it—that is, ceasing to pay the maintenance fees, so that the patented tech enters the public domain—or by selling it to another party, could have dire consequences.

- What if a competitor figured out how to use the technology to beat them to market with a popular new product?

- What if the patent turned out to be worth vastly more than the company decided to sell it for?

- What if the patent concerned technology that other companies were using, and which could be licensed for handsome fees, or used to win litigation against a competitor?

Put simply, a company’s patent holdings can be a substantial expense, or a tremendous resource. IBM, for example, generates billions of dollars every year just from selling and licensing their patents. But even many large, otherwise sophisticated companies are unskilled at making the most of their intellectual property. And for the reasons we discuss below, it’s tough to blame them.

What Makes Patent Monetization Research So Challenging?

Especially at big tech firms, the issues that the telecom executive was facing are common, and there are a few basic, interlinked reasons that they tend to arise:

- Volume: The more you have of something, the harder it is to keep track of and organize. Patents are no exception. And as patent portfolios grow, these difficulties are compounded by the fact that each patent is unique, often made up of complex processes and technical descriptions that are difficult for anyone without highly specific subject-matter expertise to understand. In large companies, with numerous research teams working on disparate kinds of technology, maintaining a detailed overview of all of the tech under patent—and of how individual technologies relate to one another—becomes a sisyphean task, particularly with new patents being filed all the time.

- Time: Between the time a patent is filed and the time it is granted, years can elapse. Technology evolves quickly, and what is valuable at the time of a filing might easily be worthless by the time the patent is granted—rendered irrelevant by some other innovation, by the fickle consumer preferences that often shape demand, or by various other forces. And yet, given time, these very same forces—a changing innovative landscape, shifts in buying trends—might eventually make a patent that didn’t have any obvious use when it was granted very valuable. Determining the value of a given patent amid this kind of technological and economic flux can be challenging.

- Specialization: Active tech research labs generate a lot of intellectual heat, not all of which is applicable to the products and/or services that their parent companies sell. One result of this is that large tech companies often end up owning a lot of patents that aren’t directly relevant to the core of their business. Many of these patents never end up being relevant to anyone’s core of business. But in the right hands, others are or will be very valuable indeed. And failing to capitalize on patents, even those that seem to fall beyond their purview, can have an extremely negative effect on a company’s bottom line.

In the case of our client, the Asian telecom executive, we were presented with a portfolio of about 800 patents. It was by no means her company’s entire portfolio, just the ones for which the researchers on her team were responsible. She would soon have to make a presentation to her board to justify the hundreds of thousands of dollars that the company was spending annually to maintain her team’s patents. The presentation would serve in part as proof of her team’s value to the company, and she hoped we could help her in two key areas:

- Demonstrating that her team’s patents had commercial, i.e. monetization potential.

- Helping her to improve the quality of their patents going forward.

In this article, we’ll explain how we did it, using a combination of machine learning software and painstaking manual analysis to provide the answers she was looking for. Along the way, we’ll show how our process for patent monetization research and analysis addresses the hurdles that make these projects so daunting for big companies to address on their own.

Note: If you want to learn more about how GreyB can assist you with monetizing your company’s patents, you can contact us here.

Why It’s Hard to Figure Out Which Patents Are Valuable

A patent might be valuable for a variety of reasons. Perhaps most obviously, it might introduce an entirely novel technology that addresses an urgent need. Alternatively, it could complement some existing invention so as to make the original technology more useful or widely applicable. But whatever the case, when evaluating a portfolio containing hundreds of patents or more, analyzing the innovative particulars of each and every patent makes for a costly and impractical strategy. A detailed analysis of a single patent generally takes a member of our team 30-40 hours, and even a patent that seems to describe a new or provocative technology won’t necessarily have marketplace value if no one is using it.

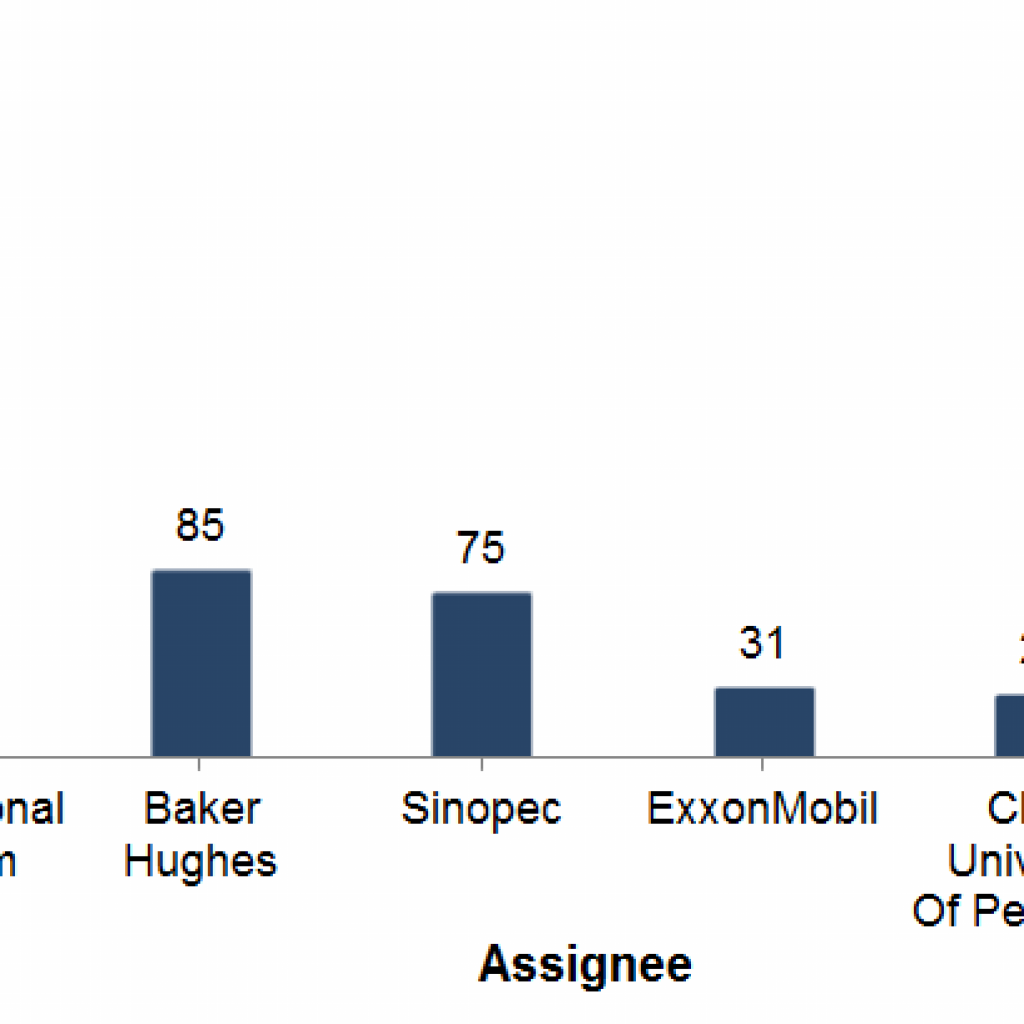

That’s why, when evaluating a large patent portfolio—like the one belonging to the telecom company—we’ll generally focus on finding which of those patents map onto products that are already available on the market from other large companies. Such instances, which are common, represent big opportunities for revenue, which can be pursued via licensing fees or litigation. A successful IP lawsuit can easily win the owner of a patent that has been infringed upon by a major company many millions of dollars.

For a big tech firm, the simple knowledge that competitors are making unlicensed use of their patented tech can also be a valuable kind of ammunition. The Asian telecom company, for example, had recently become the target of numerous lawsuits claiming patent infringement. The suits arose largely as the firm entered the U.S. market, drawing fire from American competitors. But if the telecom company could find evidence buried somewhere in their patent portfolio that some of these same competitors were infringing on their patents, it might be used to discourage American firms from initiating additional litigation. The prospect of an expensive, messy, protracted court battle, after all, is often enough to inspire a claimant to drop their suit.

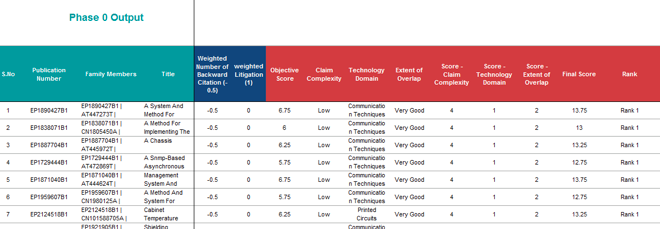

How Machine Learning Helps Narrow Down a Large Portfolio of Patents for Potential Monetization

For a company with portfolios containing hundreds of patents or more, figuring out how to best monetize their holdings requires a process of winnowing down the roster to identify the patents with the most commercial potential. To assist us in our initial analysis, we’ve devised a software tool that we call Litigation Predictor. Once a patent portfolio has been uploaded to Litigation Predictor, the software takes only a few minutes to rank the patents as a function of likely value, and to assign each one a rating of 1-3, with the best patents receiving a “1”. To reach these conclusions, Litigation Predictor’s algorithm makes a determination about the likelihood that other companies are already making use of a patent’s underlying technology. It also considers a host of additional, subtly weighted factors. Some of the most important factors include:

- Complexity: The more complex a patent—the more specific and specialized the technology it describes, the more steps involved in its processes—the less likely it is that another big company’s product will exactly reflect the patented technology. If a patent-holding company can’t demonstrate that a competitor’s product makes use of precisely the technology to which they hold the patent, they have no grounds for litigation or right to licensing fees. So as a general rule, extremely complex patents are less likely, in Litigation Predictor’s calculation, to be ripe for monetization.

- References: Very often, patents include citations to various documents related to the technology they discuss. Citations reference various sources—journal articles, internet publications—but very often, they refer to other patents. When a patent is often referenced by other patents—particularly by recent patents—it’s an indication that it concerns an active innovative sector, and that competitors are working on potentially very similar technologies. Both indicators suggest opportunities for monetization of the patent in question.

- Cluster: Litigation Predictor also takes into account the way that a given portfolio’s patents are clustered with respect to technology or industry. The value of a patent often increases, for example, if its owner also owns numerous other patents in the same area, particularly if they concern complementary technologies. So Litigation is likely to give a higher rank to a patent having to do with LCD display, let’s say, if the portfolio of which it is a part has a host of other LCD display-related patents. Of course, it helps if the patents are otherwise solid. A group of weak patents is unlikely to become valuable simply because they’re clustered around one technology or another.

| Patent Number | Technology Cluster | Rank | Probable Targets |

| US9538XXXB2 | User Interface | Rank I | Google, Apple, Facebook, etc. |

| US9388XXXB2 | Mobile Device | Rank II | Samsung, Apple, etc. |

- Litigation status: A patent that is involved in litigation is likely to be strong. If it’s already the basis for a lawsuit, that means that there’s a good chance another company is already infringing on it by using the underlying technology. Litigation Predictor will improve a patent’s rank on this basis.

- Expiration date: The standard lifespan of a patent is 20 years, beginning on its filing date. For obvious reasons, a patent with many years left has much more to offer its owner than one that’s about to expire. Accordingly, Litigation Predictor gives a higher rating for monetization potential to patents with plenty of time to go.

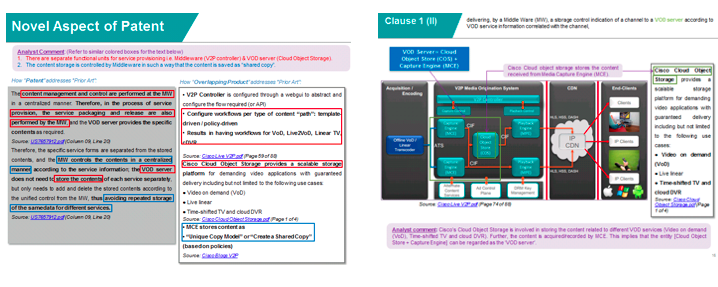

How We Determined Likely Instances of Patent Infringement with Manual Patent Analysis

Once Litigation Predictor had ranked the 800 or so patents in the portfolio of the telecom executive’s team—organizing them by cluster (e.g. User Interface, Mobile Device), and identifying probable target companies for product overlap—we began the manual part of our evaluation. We first selected the top 100 patents for a closer look. Even that subset was too large for the sort of fine-tooth analysis that would ultimately identify the portfolio’s strongest patents. But we approach the evaluation of a large patent portfolio with a defensive posture; that is, we think of our task not so much as searching for the best patents as making certain that we don’t miss them, carefully sifting the wheat from the chaff.

Missing an excellent patent can have much greater consequences than identifying a good one, so we give ourselves a generous margin of error, including 60 or 70 more patents in our initial manual analysis than we’ll ultimately focus on. Being sure that we don’t discard a strong patent is a matter of knowing what standards to apply—and applying them carefully. During this stage of the process, we deploy similar metrics to those used by Litigation Predictor, giving each patent a quick read and running digital searches with a handful of questions in mind:

- What does the patent pertain to (e.g.volume adjustment, ringtone)?

- How much information is generally available about the technology—does it appear that it’s already in use on the market?

- How complex is the technology described?

- How active is this area of the market?

In the case of the telecom portfolio, answering those questions left us with about 40 patents—the strongest of the 800 or so that we started with. But the next step in the process of patent monetization evaluation, which we call Detailed Infringement Analysis, is the most labor intensive. Members of our team spent 30 to 40 hours analyzing each of the remaining patents—examining the key elements of the underlying technology as identified by the examiner who originally granted the patent, identifying different areas in which the patent might be applicable, and doing research to find high-value products that might fall under the patent’s scope. Below, we’ll explain the process in detail.

Detailed Infringement Analysis

For each patent, once we’d come up with a list of products that seemed to have good potential for overlap, our aim was to identify evidence that the products in question worked similarly to the tech described in the patent. Finding this kind of evidence often involves a number of steps. To begin, we scoured the web for product manuals, videos, articles, and discussion forums detailing the way the products worked. It’s an essential first phase, to be sure, but it’s rarely, if ever, enough to prove a full overlap between a patent and another company’s product—the gold standard in this kind of patent monetization project.

For that, we almost always have to dig deeper, acquiring the products that still look to have strong overlap potential in order to confirm first-hand that they have the same features described in the patent. The fact that the iPhone shows a pop-up window to indicate low battery, for example, isn’t the sort of thing that’s likely to appear in the sources available via search. But the relative sexiness of a feature has no bearing on its value as patented IP. And to verify that a product is infringing on a patent that belongs to a client, we often have to examine it up close—sometimes closer than up close.

In some cases, when vetting a patent for monetization potential, simply handling or manipulating a product that seems to overlap with the patented tech isn’t enough. In these cases, we need to see what’s going on inside a product, either by reverse engineering the relevant element and building it ourselves, by tearing the product down to its hardware, or by running tests to decipher some functionality that cannot otherwise be identified via search or standard product testing.

For example, a patent for an LED screen described a particular layered structure of light particles. The layers inside an LED are vanishingly thin—too small to perceive with the naked eye. To confirm the presence of those layers in a screen that was already on the market, we had to run some lab tests on the screen’s interior, proving for sure that it overlapped exactly with the LED patent.

What Our Analysis Showed About the Portfolio’s Most Valuable Patents

At the start of our investigation in the case of the Asian telecom company, we had been asked to assist our client, an executive leading a team specializing in mobile and augmented reality-related technology, in two key areas:

- Demonstrating that her team’s patents had commercial, i.e. monetization potential.

- Helping her to improve the quality of their patents going forward.

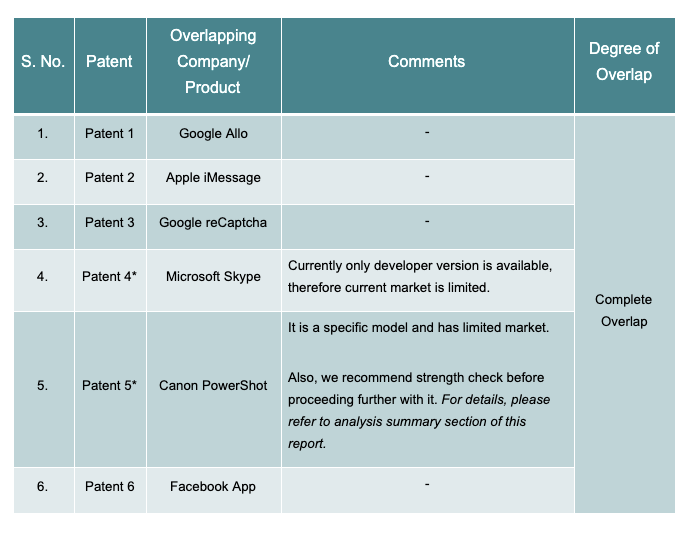

At the conclusion, we were able to identify five patents that overlapped fully with products that were available on the market from other large companies, and therefore ripe for monetization:

- Patent A focused on a messaging application that provides automatic reply suggestions based on the collected history of messages exchanged by the user.

- Patent B focused on a virtual environment where a user use his hand gestures to interact with the virtual objects.

- Patent C focused on a shared augmented reality experience between two users.

- Patent D focused on providing appropriate access to a user based on facial recognition.

- Patent E focused on detecting an activity performed by the user from an image. For doing so, scene detection was used to understand the objects in the vicinity of the user and predict the activity accordingly.

We were also able to identify one excellent opportunity to improve upon one of the team’s existing patents, which focused on a technology that adjusted volume according to a sound’s origin—voice, traffic, etc. We found a product that overlapped with that particular feature. But here we also identified an opportunity to file at least one additional patent that would further describe and broaden the scope of the technology to include features pertaining to the proportion of a given sound-origin in a multi-source mix.

We were also able to identify one excellent opportunity to improve upon one of the team’s existing patents, which focused on a technology that adjusted volume according to a sound’s origin—voice, traffic, etc. We found a product that overlapped with that particular feature. But here we also identified an opportunity to file at least one additional patent that would further describe and broaden the scope of the technology to include features pertaining to the proportion of a given sound-origin in a multi-source mix.

Although the last stages of the investigation were time-intensive, we were able to get to them quickly by drastically speeding up our initial analysis using our automated Litigation tool. As a result, our client, the telecom executive, got the answers she needed quickly. She was able to use them to strengthen the position of both her research team and her company, which was now armed with the IP ammunition they needed to continue their expansion in the U.S. market.

If you want to learn more about how GreyB can assist you with monetizing your company’s patents, you can contact us here.