In 2017, we were approached by an attorney representing a large manufacturer of digital and analog computer chips that we’ll call Chip and Dale Corp. The company had recently been contacted by another chip manufacturer. We’ll call them Chip Off the Ol’ Block LLC. Chip Off the Ol’ Block claimed that Chip and Dale were using the technology to which they held the patent. They demanded that Chip and Dale agree to steep licensing fees.

Chip and Dale badly wanted to avoid such an agreement. The proposed licensing fees stood to cost them millions of dollars, and the technology in question, which involved communication between chips—known in the biz as integrated circuits, or ICs—was integral to their operation. To stop using it would have meant closing up shop altogether. Chip and Dale had enlisted their attorney to help. But he didn’t know quite how to approach the problem, either.

Ideally, what Chip and Dale wanted to do was invalidate Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent—to render it void. In order to do that, they would have to show, somehow, that the technology on which it was based hadn’t been original to Chip Off the Ol’ Block in the first place, that in fact it already existed in 2003, the year that their patent was granted. That meant they would have to demonstrate that the patent examiner—the person at the patent office who was responsible for granting the patent—had been wrong to approve it.

Proof of this kind is what’s known as prior art.

Prior art: defined as any evidence that an idea or technology already existed at the time a patent application was filed for it.

Prior art can take many forms: another earlier patent; a mention in a magazine article, book, or newspaper report; a description in an email or letter. Finding it, via a “prior art search,” is one of the most common kinds of IP research.

A prior art search, like the vast majority of IP research tasks, begins with a deep, targeted digital patent search. Various free and subscription-based databases catalog patent data, making it keyword-searchable and sortable into helpful categories based on researcher, university affiliation, tech class, industry, and the like.

As we’ve written previously, although anyone can technically use these databases to run a prior art search, some experience navigating them is a big advantage. And at GreyB, we’ve even devised some machine learning software to assist us. But no matter how finely-honed a researcher’s search capabilities or how powerful the technology at their disposal, patent searches, especially in active innovative sectors, often return numbers of results so enormous as to be meaningless.

As we began our prior art search for Chip and Dale, this was the first obstacle we encountered. Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent described a handful of basic electronic actions: pulsation, integrated circuit communication, pulse counting. With a machine learning tool that we call Central Search, we built a keyword-based query that was both comprehensive and narrowly targeted. It incorporated terms that had been used over several decades by researchers and inventors around the world to refer to ideas and processes closely related to those described in Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent. Based on data culled from the many thousands of searches that we’ve conducted over the years, this search was vastly more powerful and more specific than anything one analyst could have put together alone.

But despite the search’s custom-made attack, what came back were hundreds of thousands of hits. The processes described in the patent, we saw, were simply too common to be useful in identifying other patents relevant to our particular area of interest. As a practical matter, the search results were impossible to make sense of.

Note: If you want to learn more about how GreyB’s investigative approach to prior art searches can help your company avoid costly litigation and licensing fees, you can contact us here.

Reading a Signal in the Noise: How to Find Useful Patterns in Patent Search Results That Don’t Seem to Give You What You Want

But there’s more than one way to skin a cat. When a keyword search alone fails to provide sufficient clarity, we often narrow down the results with another qualifier. In this case, we decided to look only at patents associated with the top five IC manufacturers in the world. The biggest tech companies tend to have the biggest research and development departments. And with all those researchers concentrating on ICs, we reasoned, it was likely that one or more of the patents that their work produced would refer to the concept we were looking for—particularly as the concept seemed to be so basic.

But here, too, we were stymied, overwhelmed by a flood of patents that met our date, keyword, and company-based qualifications, but which didn’t incorporate the exact process described in Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent—the one we were trying to invalidate. We encountered similar problems when we applied this same line of attack to searching large databases of academic research, like Google Scholar and WorldCat—a process with which we usually complement our patent searches.

Sometimes there are also industry-specific databases or archives relevant to a particular prior art search. In this case, our team spent many hours paging through summaries and schematics on a website called Datasheets, a repository of production and research documents concerning electrical components.

Designed for the hardcore electronics development community, Datasheets is not readily searchable. Much of its content consists of highly technical diagrams. To understand them—to verify what, exactly, they’re talking about—often requires long, careful scrutiny, even for an electrical engineer. But grueling as it was, our survey yielded no useful hits.

At this stage of the process, we could have reasonably gone back to the attorney who’d hired us and reported that our many searches for prior art had been unsuccessful. Some IP researchers likely would have done so. In some instances, it would even have been appropriate.

Not every accusation of patent infringement or demand for technological licensure can be defended against by finding prior art. Some patents describe ideas and inventions that really are novel; it’s the principle on which IP protections are built, and we spend a lot of time and energy championing our clients’ IP rights. To encourage a company to continue searching for something that we’ve concluded almost certainly doesn’t exist would be dishonest.

But it’s also true that when it comes to prior art searches, we start with the assumption that the evidence we’re after does exist—that the patent examiner made a mistake—and that given enough time, we’ll locate it. It’s part of what we think of as our Investigative Approach to IP research, which we consider our guiding philosophy. And in the case of Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s IC communication patent, our initial efforts provided good reason to believe that the technology it described wasn’t new at the time that the patent was granted in 2003.

To be sure, there had been plenty of electronics innovation between 2003 and 2017, when we were doing our research. But 2003 was hardly the dawn of the computer age. By then, integrated circuits had been around, and communicating with each other, for roughly half a century. It seemed highly unlikely that no one had come up with the simple concept described in Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent before 2003. And though our digital searches hadn’t pinpointed the prior art that we needed, it did have the effect of heightening that suspicion.

Due to the overwhelming volume of search results described above, it wasn’t possible to review them all. But we did look at several thousand, more than enough to observe a pattern. Whatever the source—patent database, Google Scholar, Data Sheets, etc.—we noticed, the IC-related inventions being patented in the early 2000s were uniformly much more advanced than the technology protected by Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent.

Prior art searches often involve reconstructing history—going back in time to zero in on the moment that an idea first saw the light. In the course of conducting many such investigations, one becomes keenly attuned to a bedrock principle of innovation: simple solutions emerge first, in answer to general challenges, followed by increasingly specific, complex technologies designed to address increasingly specific, complex challenges.

The other IC patents of the early 2000s protected technologies that clearly came generations after the concept described in the Chip Off the Ol’ Block patent. By necessity, they were building on it, even if unconsciously. As far as we were concerned, that meant that somewhere, perhaps buried deep in the past, prior art had to exist.

When Keywords Aren’t Enough: How to Use an Investigative Approach to Devise Successful IP Research Strategies Where Standard Keyword Searches Fail

As we considered what to do next, it occurred to us that Chip Off the Old Block’s patent devoted a lot of space to outlining the process that the underlying technology was designed to accomplish, and virtually none to describing its physical components. In other words, the patent said what the technology did, but not what it actually was.

Like a criminal inquiry, an IP investigation almost always involves following clues without being sure where they will lead. And without knowing quite where it would take us, we decided to find out what the patented technology would look like—what components it would consist of.

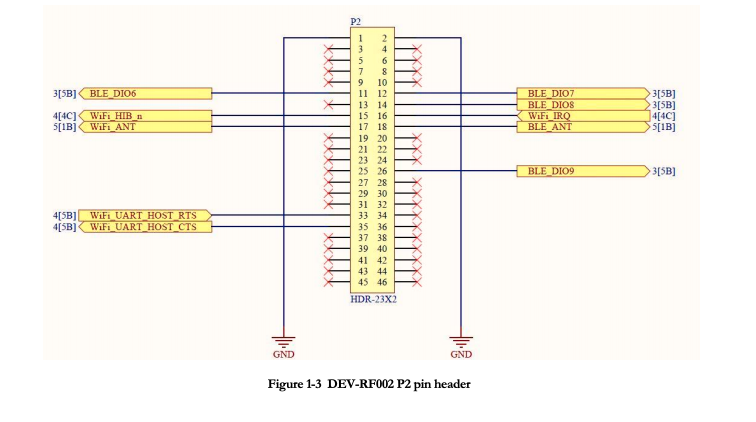

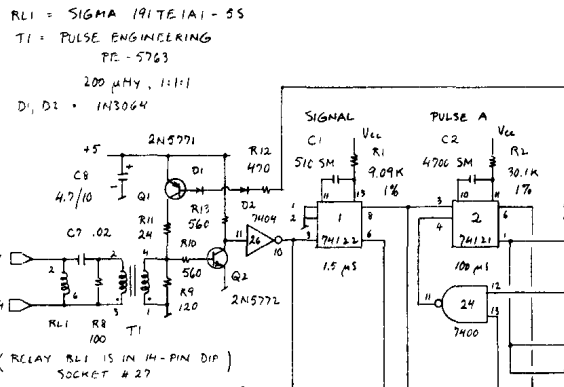

Our team had a background in electrical engineering and having recently spent hours poring over IC diagrams in Data Sheets, we didn’t need long to draw up one of our own representing the dynamics described in Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s patent. It was, after all, a relatively simplistic technology. By looking at the model, we quickly realized that the technology in question had to include a monostable multivibrator—an element known in electronics slang as a “one-shot.”

The one-shot generates an outgoing pulse. It is an extremely common component, found in a wide variety of electronics. It was in part, for this reason, we concluded, that the one-shot hadn’t often surfaced in our patent searches. To electronics professionals, its presence would have been obvious. But our diagram also indicated that to facilitate the kind of communication described in Chip off the Ol’ Block’s patent—the underlying idea for which they were demanding payment—the one-shot had to be used in conjunction with a pulse counter: a device that would receive and count pulses emitted by the one-shot, translating them into an action of some kind.

At that point, we were close. The combination of the one-shot and the pulse counter implied by the patent seemed to us like tech that was not only simple but very old; our diagram strongly suggested that as we’d suspected, Chip Off the Ol’ Block had managed, by some fluke, to patent an idea that already existed in 2003. But for Chip and Dale to avoid multimillion-dollar licensing fees, we still had to find prior art that showed it, in writing and without a shadow of a doubt. Armed with a new combination of search terms—“monostable multivibrator” and “pulse counter”—we returned to square one: a broad, deep search of patent and academic databases.

Again, we got thousands of results. But this time there were many fewer thousands—a manageable universe of documents. One by one, we sifted through them, careful not to discard anything as irrelevant before we were certain it didn’t contain what we were looking for. Eventually, roughly two weeks after we’d run our very first searches, we found it: a description of the very concept that Chip Off the Ol’ Block had somehow succeeded in patenting in 2003. It was buried in the appendix of an obscure Ph.D. thesis, which dated to 1970.

As we suspected, Chip Off the Ol’ Block’s idea hadn’t been novel for quite some time. And with evidence that showed as much, Chip and Dale returned to business as usual, with no costly licensing fees to budget for.

Had we quit when our searches didn’t bring us the results we were looking for, we never would have ended up tinkering in our office, imagining how to design a technology that dated (at least) to the 1970s. But as it often does, our inclination to believe that prior art was out there somewhere—and a methodical, creative approach to finding it—led us to our target.

If you want to learn more about how GreyB’s investigative approach to prior art searches can help your company avoid costly litigation and licensing fees, you can contact us here.

Relevant ongoing cases where above mentioned strategies can be applicable:

- 8-21-cv-00046 (CDCA) Core Optical Technologies, LLC v. Comcast Corporation et al

- Patent involved in case: US6782211B1

- Technology areas involved: Modulation, optical system, polarization

More relevant strategies that can be explored for such cases:

- How we found references in non patent literature without performing an NPL search? (Related to circuit design)

- How we Invalidated a Wireless Communication Patent using Standards? (Related to IEEE standards)