Like trial transcripts, birth certificates, and property deeds, patents are supposed to be freely available to anyone interested in reading them. And officially, they are: patents are a matter of public record, available online for reference via the national patent offices where they’re stored. But for reasons we’ll detail below, for the vast majority of people—even people for whom patent data has powerful professional implications, like R&D researchers, innovation team leaders, and CEOs—patents represent a vast, unnavigable sea of information. In fact, patents, the most complete records of the global history of innovation, are truly accessible only to a very few.

Due to long experience, at GreyB, we count ourselves among these few. Indeed, it is for assistance finding and analyzing patents that many of our clients come to us. But that doesn’t mean we’re happy with the status quo. A few years ago, we started working on a new tool that would bring reality into alignment with the idea of patents that are truly available to the public.

The winner of a 2019 Edison Award, our solution, Catalyst—a machine-learning powered, keyword-based search tool that allows researchers to find patents based on the problems they address—is now available free here. If the worldwide universe of patents is a vast sea, then our tool is at once compass, sextant, and sturdy vessel, uniquely well equipped to help researchers find what they’re looking for, whether it’s to build upon the ideas and innovations of others, draw inspiration from existing patents, better understand the landscape of a given technology or marketplace sector, or simply understand what is new and what is not.

Though we designed Catalyst to be useful and intuitive for most any searcher, we suspect that users will largely fall into three categories:

- The Problem-Focused Professional: Research scientists and engineers whose inability to access patent data causes them to waste time, energy, and money, replicating existing solutions both good and bad, and miss out on opportunities to be inspired by and build upon the work of others working on the same problem(s)

- The Innovation-Focused Professional: Research scientists and engineers whose inability to access patent data prevents them from knowing what’s new and what’s not, leading them to pursue silly or fruitless notions while obscuring areas likely to produce more innovative and lucrative ideas

- The Everyman: Basement tinkerers, and backyard Edisons, anyone with an invention or idea that just won’t leave them alone

In this article, we’ll explain what exactly Catalyst is, why we think the tool is necessary, how it accomplishes its goals, and provide detailed explanations about who it will help, and how.

Note: If you want to try Catalyst yourself, you can do so here.

Why Is It So Hard To Find and Understand Patents In the First Place?

Intellectual property is a bargain between government and inventor. To encourage innovation, governments agree to protect new ideas from appropriation by granting the inventor (or their employer) a patent guaranteeing exclusive ownership of the idea, usually for a period of 20 years. The patent allows the owner to deploy the idea for commercial purposes themselves—by creating and selling a product, for example— license its use to others, or sell the patent to another person or entity.

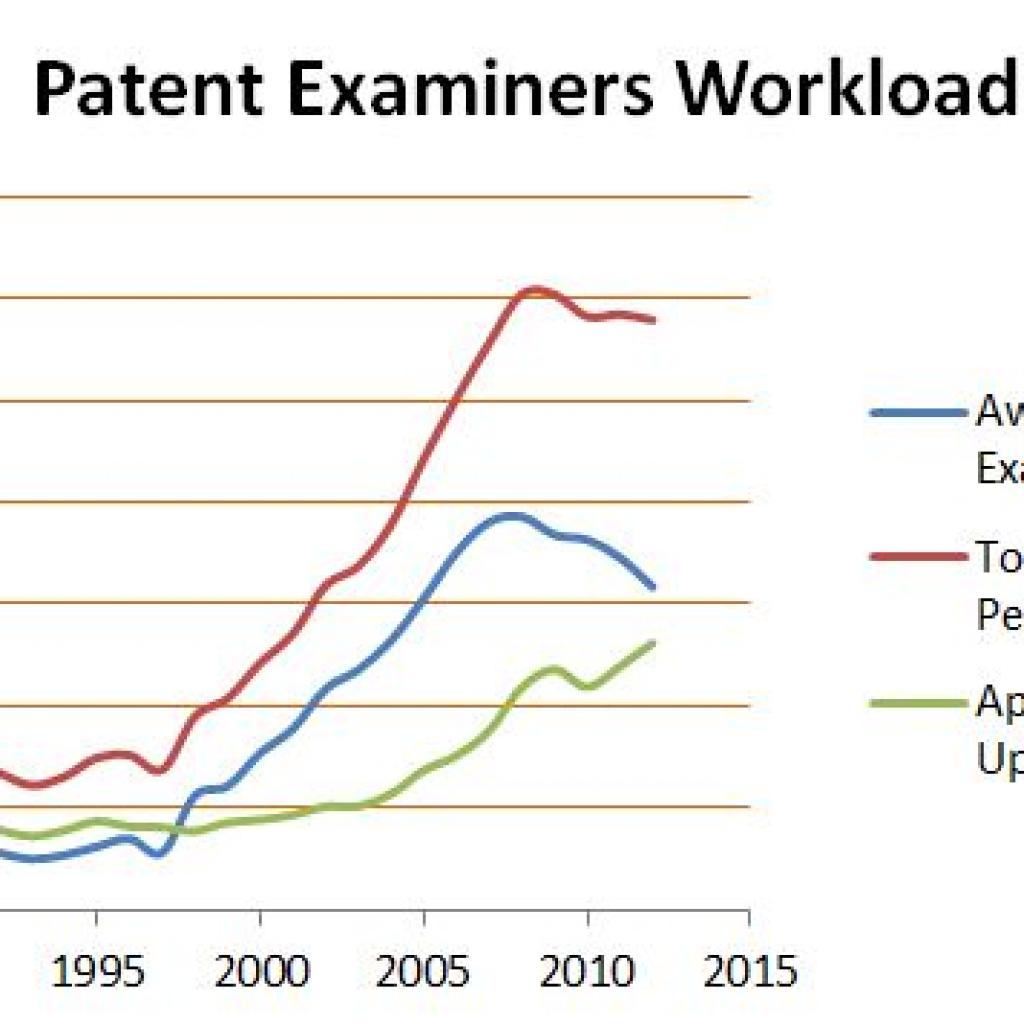

For the patent holder, the benefits of this bargain are obvious: airtight legal defense against theft of their idea by competitors. The other side of the agreement is more subtle. Each and every new patent gets filed with a national patent office—most countries have one. Roughly eighteen months later, the filing becomes public. Eventually, after one of the patent office’s examiners has completed her review of the application, she renders a decision as to whether the patent contains a truly novel idea. If so, the patent gets granted, and that information becomes public, too.

This is crucial.

Publicizing their idea is the price an inventor pays for the protection the government offers. The public benefits from this arrangement, the thinking goes, when other innovators build upon patented ideas to arrive at new products and solutions and/or become inspired to come up with novel, broadly beneficial ideas of their own. A variety of databases both free and subscription-based—Google patents, PatSnap, AcclaimIP—compile searchable, up-to-date patent info in real time.

So in theory, all of the patent data in the world is easily attainable to anyone who cares to find it. But in practice, this isn’t the case at all.

Just finding patents requires considerable expertise—to say nothing of understanding them— and the most obvious obstacle is sheer volume: patents number in the millions, and sifting through them, especially for a layman, can be a nightmarish (and usually futile) task. But another big part of the problem is that identifying patents often depends on finding documents that, either by accident or design, are effectively hidden.

When an idea or technology is new, there is often no consensus about how to describe it, resulting in a broad vocabulary of closely linked but not obviously related terms: A professor at Berkeley might use one set of words in his patents, researchers in Beijing another; a team of inventors in Seoul might have a third way of talking about similar ideas. Almost invariably, there is also dense technical and/or legal jargon to wade through. And in order to maximize the scope that a patent covers, savvy patent writers tend to use wording that is as broad as possible.

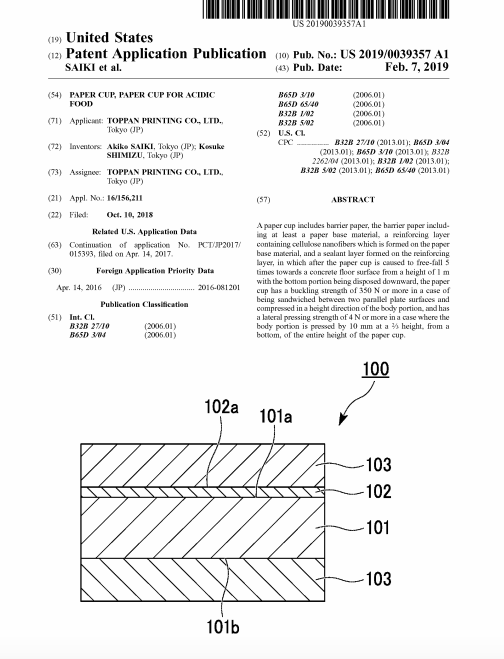

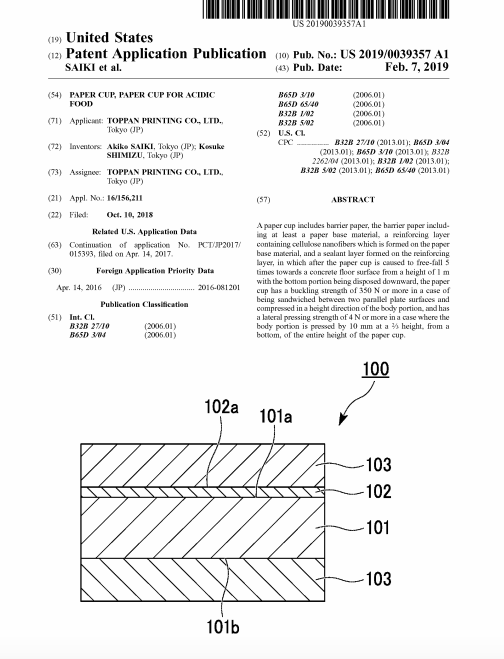

For example, in the patent above, for a lowly paper cup, rather than simply say “the base” of the cup, the author of the patent writes, “the bottom portion.” To be sure, the author is describing something specific. But the phrase is incredibly vague. It could be interpreted to mean almost anything—an advantage for a patent owner who wants to defend or capitalize on her intellectual property, but a pain for anyone who’s trying to determine what the language in the patent actually means. In fact, once a patent is drafted—a job that falls to attorneys—the inventor of the underlying technology will often have a hard time making sense of it.

Other scenarios involve more obvious kinds of subterfuge.

To avoid detection by competitors, companies file patents containing language that is deliberately opaque—describing a particular mechanism vaguely, for example, as an ‘agent’—or so specific as to provide camouflage: a noodle might become ‘a twisting, edible, cylindrical element.’

The upshot is that although patents are technically public, for most intents and purposes, they’re practically impossible to navigate for anyone without substantial experience in the area. (At GreyB, to complement our expertise, we rely on a host of subscription-based databases and in-house machine learning-powered tools to help us.) Frustrating as all these linguistic and semantic issues are, they’re actually part of a larger, more basic obstacle to the ideal of truly public patent information.

And it’s this more basic problem that Catalyst meets head-on.

How Catalyst Works and Why

So far we’ve talked a lot about what does appear in patents: a lot of confusing, obfuscating language that makes it all but impossible for researchers to find what they’re looking for. And if there’s a central theme to the way patents are written, it’s that authors tend to focus almost exclusively on what the idea or product consists of and how it works.

By way of example, let’s take another look at that paper cup patent:

As you can see, there is much discussion in the abstract of the physical characteristics of the cup: “base material,” “reinforcing layer,” etc. These are not exactly terms that come to mind for most people when they think about paper cups. Nor is there any mention of the cup’s purpose: holding liquid.

This pattern is typical, and it in part accounts for the confusing level of detail that characterizes the language of patents. It also means that virtually no space is devoted to why the patent exists—the problem that the underlying idea aims to solve.

And it is in terms of problems and solutions that inventors, would-be inventors, people, in general, tend to think. For good reason: the point of invention is the solving of problems. And yet the language of patents and the language in which people are inclined to use to look for them bear little resemblance to each other, all but assuring that practically no one will be able to find what they’re looking for.

This is where Catalyst comes in.

How Catalyst Finds Vital Buried Data

When it comes to patent research, the problem of information overload is not limited to wading through millions of individual patents. Each patent in and of itself contains far more data than anyone—even a person well-versed in patent research—can quickly read and analyze. A typical patent runs to 10 to 30 pages, each of them dense with the kind of opaque, oddly worded descriptions and legal jargon we’ve been talking about. If a reader didn’t know any better, she might forgivably conclude that in fact, this was all patents consisted of.

But almost invariably, buried somewhere amidst all of that confusing detail are a few sentences or phrases that do suggest the reason for the patent’s existence—a statement (or at least a partial statement) of the problem that the underlying idea or technology has set out to solve. And as it happens, these portions of the patent tend to be written in relatively clear language, terms discernible even to researchers with limited patent experience. (It turns out that there are only so many ways to describe a problem.)

In designing Catalyst, we fastened on this particular characteristic of patent composition, creating a machine learning system that scans all of the patents housed in the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to extract these useful fragments of text, which we refer to as “problem statements.” Once Catalyst has identified a problem statement, the system deposits it into a separate database of its own, one organized according to problem statements.

This new, problem statement-based database is what users interact with when they use Catalyst. It’s keyword searchable, and because the problem statement portions of patents tend to be written in fairly clear language, researchers using the system don’t need to translate their thinking into the idiosyncratic language of patents—strange constructions and unlikely synonyms, etc.—to find what they’re looking for. By categorizing patents according to the kinds of problems they address, Catalyst also minimizes irrelevant search results—arguably the greatest scourge of professional patent researchers everywhere—leaving them with much less data to sort.

A search has to do with paper cup-related problem statements, for example, won’t return patents that simply mention paper cups, but which are really about something else—coffee machines, say.

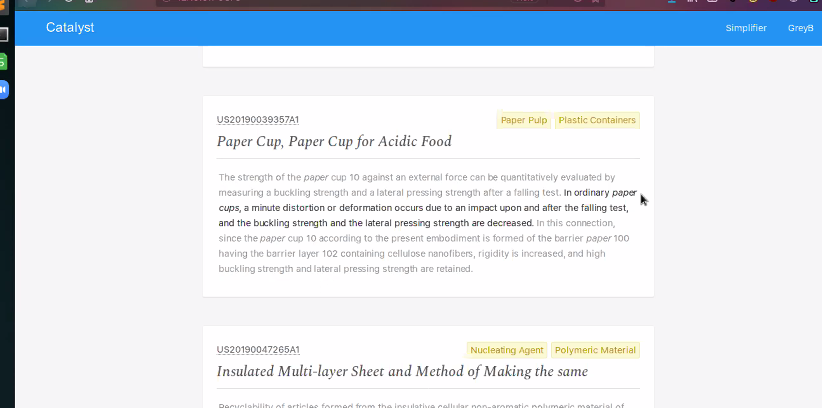

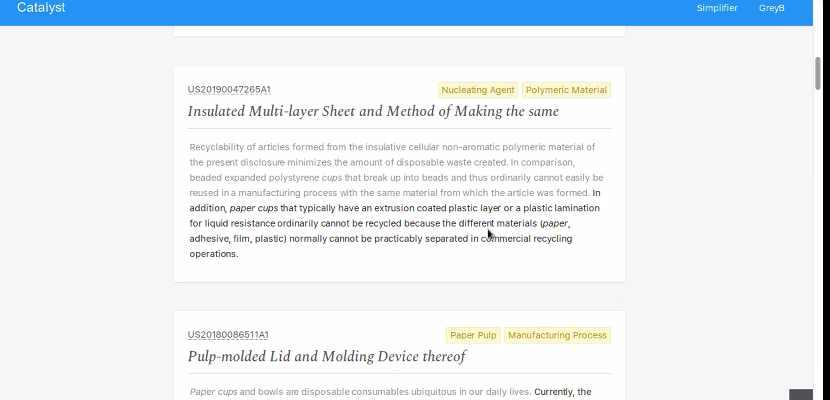

Below, you can see some examples of Catalyst search results for paper cups:

By clicking on the patent number in a search result, researchers can read the full text of the relevant patent. Each search result also includes a couple of tags—some of these, admittedly, sound rather technical—as well as bolded text from the patent itself highlighting the precise problem it’s trying to solve. By scanning search results organized in this way, researchers can quickly separate the proverbial wheat from the chaff.

Ultimately, we envision Catalyst as a system that offers two distinct, searchable databases:

- The one we’ve just described, which we will continue to tweak and improve.

- One designed along similar lines, but with solutions, rather than problems, as the organizing principle.

For the reasons outlined earlier in this post, solution-based text extraction represents a more complex challenge: in patents, the language of solutions is often very difficult to parse, making a straightforward statement about brass-tacks functionality extremely hard to isolate.

It’s also true that although we can imagine that some users might want to narrow their searches, at least in certain cases, according to solutions, the fact of the matter is that problem-based searching represents a more powerful and widely applicable tool. It isn’t, of course, that thinkers and inventors aren’t interested in solutions at all. But in the context of a given project, it’s the problem that a researcher is thinking about that’s going to guide their work, and hence the patents that have already tried to address the problem—or similar problems—that are going to be most helpful. Put another way, Catalyst’s problem-based search does surface relevant solutions. But it does so as a function of the underlying problem.

Who Will Use Catalyst and What Will They Do with It?

So, whom, exactly, is Catalyst for, and how might different kinds of researchers put it to work? We imagine three major users:

The Everyman

While Catalyst represents an entirely novel product, functioning like no other currently available, it’s also unusual in that we designed it primarily with laymen in mind—that is, everyday people, with no hands-on experience in intellectual property development or patent research. This goes back to where we began our discussion: the discrepancy between the theoretical easy availability of patent data and the fact of its being virtually impossible to access without (often very costly) expert assistance. It’s this gap between reality and stated ideal that Catalyst primarily aims to close.

Currently, average people become familiar with new technology only when it finds widespread expression in the marketplace; they’re cognizant of emergent ideas only when they become available, in one way or another, for purchase. Unsurprisingly, as a result, people tend to think of product and idea as more or less inseparable. One result of this is that when a person has an idea, but lacks the technical know-how—engineering, chemistry, or software expertise, for example—to bring it to physical fruition, they’re often inclined to conclude (albeit without a great deal of consideration) that it has no value, or at least that it’s more trouble than it’s worth to pursue.

This could not be further from the case. For example, digital screens—on phones, tablets, etc.—that change orientation as the user tilts or turns a device didn’t become available until about ten years ago. For most consumers, it seemed, at that point, like an entirely new idea. But in fact it had first been described in a patent as far back as 1993. That the patent holder was unable to actually create a product incorporating the idea did not detract from its novelty, nor from its ultimate marketplace value; the owner of such a patent—if it’s still current—might easily monetize their IP via sale, or by licensing it to a company or companies that want to use it.

By opening up the universe of patent literature to the everyman—the thoughtful everyman, anyway—Catalyst should help prevent great ideas, like the orientation-changing screen, from getting buried beneath avalanches of information, remaining easily accessible to anyone who might be thinking about related problems and potential solutions. In this way, we hope, Catalyst will vastly increase the public value of the patent system, which currently overwhelmingly favors large corporate patent holders and the niche-savvy class of highly paid IP lawyers and analysts who assist them in writing, finding, evaluating—and hiding—patents.

The Professional: Problem-Focused

The obscurity of patent data also creates myriad frustrating inefficiencies for professionals working in various areas of research and development. A large sub-category of such R&D employees is made up of people whose work revolves around identifying and solving problems native to a given industry or product line. As things currently stand, few if any researcher-developers of this kind are equipped to navigate the patent universe. As a result, they often end up working in a vacuum. Alone with their thoughts, they’re largely unaware of what other researchers working in the same area are doing, or what has been done before them.

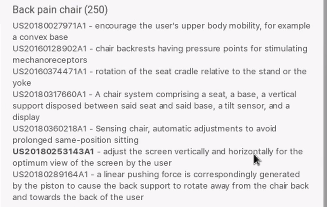

Inevitably, they replicate one another, spending a great deal of time and energy on solutions that already exist, and which may or may not actually work very well. Cut off from patent records, they also miss innumerable opportunities to be inspired by and/or build upon the work of their peers and predecessors. Below, a backend screenshot from Catalyst demonstrates a case-in-point, a sample of patents surfaced by a search for chairs that aim, via various means, to alleviate/reduce back pain:

The Professional: Innovation-Focused

Different kinds of R&D departments at different kinds of companies have different mandates. And another common one is sheer novelty: innovate. Often, of course—although not always, somewhat surprisingly—R&D labs have more specific orders, dictating one or more sectors to focus on. But if you don’t know what’s already out there, it’s very difficult to evaluate whether an idea is new to you or actually new.

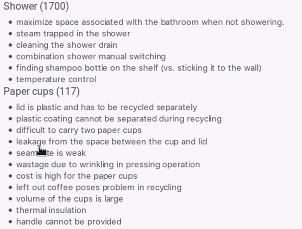

In this context, Catalyst can help researchers quickly understand which ideas to abandon and which ones to pursue, using a search to sketch the history of innovation around a given problem. In addition to revealing what specific ideas have already been claimed, Catalyst has the potential to simultaneously unveil new ways to think about a given product or sector: solutions related to the manufacture of a paper cup, say, rather than to its use by consumers. Crucially, Catalyst can also help R&D professionals identify blank spaces—areas where research has been limited or non-existent, and where few if any patents exist. For obvious reasons, these might well represent especially enticing, and lucrative, opportunities.

The backend screenshot below demonstrates a handful of insights along these lines for both paper cup and shower-related patents:

If you’d like to learn more about Catalyst and see how it works for yourself, you can do so here.