In 2016, a major Chinese smartphone manufacturer came to us with a problem. The company was being sued by a competitor, also based in China, for patent infringement, and they would soon have to appear in court to defend themselves. The penalties for patent infringement can potentially be very painful—fines reaching into the millions of dollars, followed by costly licensing fees or, even worse, an injunction prohibiting further use of the patented technology.

For the smartphone maker, in this case, the stakes were particularly high. The patent that they were being accused of infringing on covered a very general technological concept: an on-screen display that showed which cellular network each call in the call log was associated with. Somewhat counterintuitively, patents covering very basic ideas like this one, rather than highly specialized concepts, often turn out to be the most valuable, as competitors—and even unrelated companies—find themselves in need of the tech.

Our client used the technology in question in each and every one of their phones. So if things didn’t go their way in court, the financial and operational consequences were likely going to be dire.

To avoid that possibility, they were hoping to invalidate their competitor’s patent. To do so, they would need to prove that the idea their competitor was claiming as their own had already existed at the time their patent was granted. In other words, they would have to show that the examiner—the person at the patent office who had given the patent a green light—had made a mistake in doing so. If our client could do that, the patent would be rendered void and they would be absolved from any claim of infringement on it.

The kind of proof that the smartphone maker needed is what’s known as prior art, defined as any evidence that an idea or invention is already known at the time of first application for a patent on it. Finding prior art is one of the most common tasks in the world of patent research.

Like our client the smartphone manufacturer, companies often look for prior art in order to win litigation or avoid paying licensing fees for a piece of technology they’re using. But it’s useful in other cases, too.

If someone has a new idea (new to them, anyway) and they’re thinking about applying for a patent, a prior art search can give them an overview of the environment and suggest whether their “invention” is, in fact, old news—or if they’ve come up with something truly novel that’s worth the effort of a patent application.

Similarly, holders of patents or patent portfolios frequently conduct prior art searches to get a sense of how strong their patents are. If a patent is strong, it might be ripe for monetization, either through sale, licensure, or product development. If not—that is, if prior art exists—the patent may well be targeted for invalidation upon entering the marketplace.

Whatever the case, every prior art inquiry begins, like virtually all patent research: with a careful search of existing literature, including patents and patent applications; academic, industry, and mainstream publications; and sources as disparate as internet forums and regulatory agency archives.

Note: If you want to learn more about how our unique approach to prior art searches can help your company avoid costly litigation and licensing fees, you can contact us here.

The Difficulty of an IP Search Across 10 Years of Advancements in Cellular Technology

Technically speaking, anyone can conduct a patent search. Soon after a patent application gets filed—and well before it’s granted or denied—it becomes a public record. Various databases like Google Patents (which is free), and subscription services like PatSnap and TurboPatent, make records available via keyword-based search. But patent research is rarely straightforward.

The patent on which our client the smartphone maker was accused of infringing dated to February 2006. So in order to help them, we needed to find prior art that existed before then. That complicated things. In cosmic terms, of course, ten years is a blip. But as far as cellular technology is concerned, it might as well be an eternity.

Generations of innovation had come and gone in the interim. To find prior art, we would essentially have to reconstruct that history—as well as the immediately preceding years—looking for the moment when the patented idea emerged. Still, in our line of work, that’s hardly unusual, and to get the lay of the land, we began by running searches in a variety of patent databases like the ones described above.

Each database works a little differently, complete with individual quirks and preferences. Some are more appropriate for one kind of search than another, so it pays to have some experience with all of them. In general, we’ve learned over time that the experience of our team, both past, and present, is one of our greatest resources, and in recent years, we’ve developed a number of in-house machine learning tools to archive, fortify, and multiply our collective wisdom.

Interested in learning how to conduct a prior art search on your own with free patent databases? Our team has prepared a handy guide aimed at providing comprehensive yet easy-to-follow patent searching tips for different databases. You can get a copy for yourself from here (it’s free, so feel free to share it with your colleagues too):

How We Address the Challenges of Deep Historical Patent Searches with a Combination of Tech and Strategic Thinking

To assist in a patent search, we might use ‘Past Projects’, an internal search tool that draws on each and every previous IP investigation we’ve ever conducted, while providing suggestions about where we might find solutions to whatever conundrum we’re facing at the moment.

For a search like the one we did on behalf of the smartphone manufacturer, another tool, ‘Central Search’, is especially helpful.

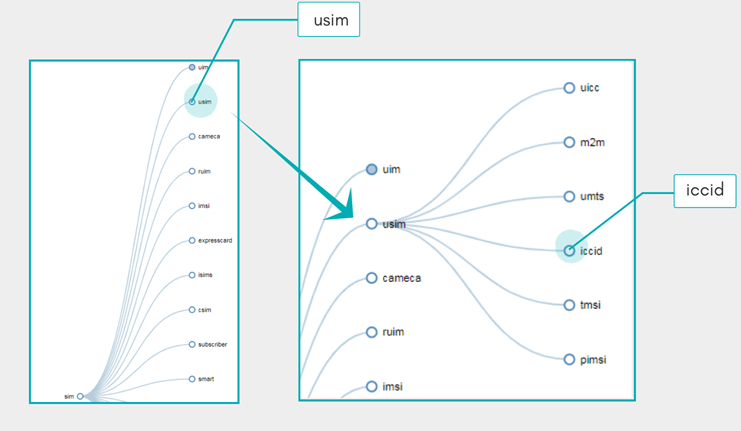

In a rapidly evolving sector like cell phones, in which new patents codifying novel ideas are filed around the world every day, the vocabulary is both vast and ephemeral. Terms to describe a mechanism or process fade quickly in and out of favor, while inventors in different places use completely different language to describe similar or even identical ideas.

There’s no way one patent researcher—even a veteran patent researcher—can hope to capture this variety alone on the basis of a keyword search, particularly when seeking patents that are at least a decade old. But much like ‘Past Projects’, ‘Central Search’ taps the entirety of our search history, providing dozens, if not hundreds of related terms for any keyword a researcher might enter.

If a patent search based on the vocabulary and experience of a single analyst is like fishing with a rod and reel, then a Central Search-based query is more like using a deep-sea trawl net.

The results of our patent search for the Chinese smartphone maker were both frustrating and promising—not an unusual combination in this process. We got a lot of hits, but most of them were unhelpful—references in patents filed after 2006. Two of the results, however, suggested that the technology our client was using predated the patent held by the company suing them. One was a patent, mentioning the concept, that had been filed before 2006.

In the U.S., that would have been enough to invalidate. But under Chinese law, to count as prior art, the evidence must have been publicly available before the date on which the patent was granted. And although the potentially exculpatory patent was filed earlier, it didn’t become public until after February 2006. So no dice.

But in the course of our search, we also identified a phone model that seemed to employ the technology we were interested in. Based on the manufacturer’s product ID, we knew it had gone into production before 2006. But we needed some documentary evidence, ideally the phone’s user manual. User manuals are often available online, either via a government database or manufacturer’s website. But we were dealing with the years before the pan-digital era, and the manual wasn’t online. Despite a top-to-bottom “real-world” search, we couldn’t locate a viable hard copy either.

Going Beyond Search: Using Our Investigative Approach When Typical Patent Searches Would Have Stopped

At this point in the process, many patent researchers would stop. No client could fault them for doing so. Having conducted a thorough search, they could reasonably claim to have done their due diligence. During an earlier stage in GreyB’s history, we might have stopped, too. But over time, we’ve evolved, developing what we call an ‘Investigative Approach’ to patent research, in which an exhaustive digital search is often merely the first step.

Where prior art searches like this one are concerned, we actually assume that whoever was responsible for granting the patent in question made a mistake—that prior art exists, somewhere, and that eventually, we’ll find it. In this case, our initial search confirmed as much. It was clear to us now that at the time the cell phone patent was approved, the idea on which it rested wasn’t truly novel. The patent shouldn’t have been granted. All we had to do was prove it.

Beginning with some additional leads that we sourced from our patent search, we embarked on the next stage of the investigation, drawing up a list of phones that were available in 2005. To catalog all the cell phones on the market at the time would have been unrealistic. But we caught a break from the patent we were hoping to invalidate.

Even today, relatively few phones can function on both of the dominant 2G networks: CDMA and GSM. (Though we’re now in the 5G era, most phones still need to support 3G and 2G networks.) In 2005, such phones were rarer still. But one feature of the patented call log display was that it also showed the dual network capabilities of the phone on which the technology was installed. In other words, the phone that would prove our case, whatever model it happened to be, would support both the CDMA and the GSM. That narrowed things down considerably. Still, when we combed manually through the specs of potential candidates made by major name brands—Motorola, Nokia, etc.—we came up empty-handed.

Following the Trail Where It Leads: Our Hunt for One Very Old Cell Phone

An investigative approach to patent research means following leads without knowing where they’re going. Some—indeed, most—are dead ends. There are times when we tell a client that based on our investigation, the evidence that they’re looking for does not appear to exist. In this case, however, our gut told us that prior art was out there somewhere. And we had a hunch about where to look next.

Although less well known than the Apples and Samsungs of the world, Chinese cell phone makers had participated in a flurry of innovation during our period of interest. And in China, a Wild West ethos characterized the era; much of the creativity went unpatented. That meant it wouldn’t have turned up in our searches—or, in all likelihood, in those conducted by the patent examiner.

Again, we compiled a list of phones. This time, by consulting their user manuals, which we sourced from a Chinese government database, we found a model that looked promising. But we couldn’t tell for sure. We needed to see the phone, to examine it first-hand, so we launched a survey of second-hand electronics stores. The model we were looking for certainly wasn’t a hot commodity. But we thought there might be one sitting forgotten in a drawer somewhere.

When that tactic proved fruitless, we turned back to the web, scouring the Chinese equivalents of eBay and Craigslist.

Here, finally, we found a phone with the precise specifications we sought: a pre-2006 model with dual-network capacity and a call log display that showed the cellular network with which each call was associated. But we needed to be sure that the phone was in its original condition—that is, that its software hadn’t been updated. After some back and forth with the seller, we were able to confirm as much through screenshots.

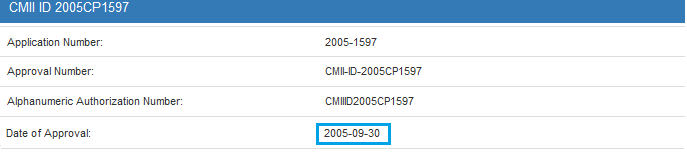

When the phone arrived in the mail, we opened its plastic back panel to find, printed beside a barcode, a government-issued production authorization number, which dated to September 30, 2005, five months before Feb 2006, when the patent we needed to invalidate had been granted. The evidence would hold up in Chinese court, and our client was able to skirt millions of dollars in losses.

Had we quit when our searches didn’t bring us the results we were looking for, of course, we never would have ended up on the somewhat unusual shopping trip on which we ultimately found ourselves. But as it often does, our inclination to believe that prior art was out there somewhere—and a methodical, creative approach to finding it—led us to our target.

If you want to learn more about how GreyB’s investigative approach to prior art searches can help your company avoid costly litigation and licensing fees, you can contact us here.